Louis Austin: The Spiritual Architect of Durham's Black Press

The history of Black journalism is synonymous with the name Louis Austin, a community member who devoted his career to "The Truth Unbridled."

This story is a part of our African American Heritage Guide Project, a printed guide and collection of stories about Durham's Black history, culture, community and entrepreneurship created by Black writers, poets and artists. Find more stories and information about the guide.

Following the Revolutionary War, there was a renewal of America’s history of advocacy journalism with the 1827 publication of Freedom’s Journal.

The anti-slavery newspaper was founded by free Black New Yorkers, and assembled at the home of Boston Crummell, a community organizer and father of Alexander Crummel, an Episcopal priest and towering intellectual who inspired W.E.B. DuBois.

“We wish to plead our own cause. Too long have others spoken for us,” the paper’s editors John Russworm and Samuel Cornish stated on the front page of Freedom Journal’s first edition, published on March 16.

In 1927, one hundred years after Russworm and Cornish published Freedom Journal’s first edition, Louis Austin, a 30-year-old insurance manager and sports editor, purchased The Carolina Times whose offices were in downtown Durham.

From the onset, Austin made plain his editorial mission. He declared the newspaper to be “the mouthpiece of Negro Durham,” and adopted as its motto, “The Truth Unbridled.”

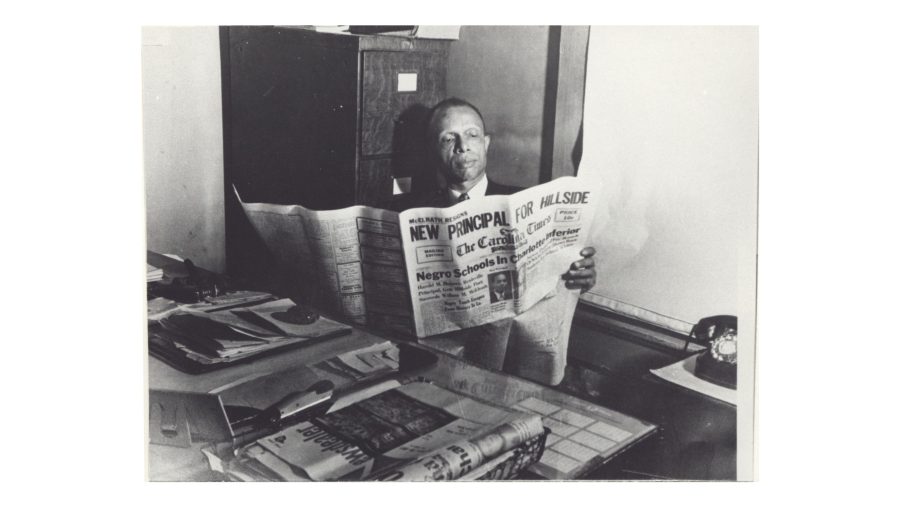

Louis Austin led by example as both a journalist and a community member. Photo: Durham County Library Historical Photo Collection

Today, Austin stands as the spiritual architect of Durham’s Black press whose legacy has influenced generations of journalists. With his Carolina Times, Austin created a newspaper that challenged the powerful, created a platform for the underdog and lifted every voice to be heard.

During his tenure, Austin fought to establish a law school at North Carolina Central University. He championed the hiring of Black city employees, and led crusades for equal pay for Black public school teachers and for paved streets and street lights in Black communities.

“What is a Black press without a Black consciousness?” the retired Tuskegee airman, legendary journalist and late UNC-Chapel Hill journalism professor Chuck Stone asked this writer in the late 1990s.

Decades later, Austin’s passionate advocacy for an independent Black press with a Black consciousness continues in Durham with Black-owned, Black-centered publications like The Carolinian, The Triangle Tribune, Spectacular Magazine, The Saunders Report, The Durham VOICE, and NCCU’s Campus Echo.

Austin was born in Enfield, North Carolina in 1898, a year that tested the soul and mettle of the entire state.

The Wilmington Race Massacre occurred on November 10, when white terrorists staged a violent coup d’état of a multiracial government in Wilmington.

Months before on August 22, Durham’s Black leaders founded the North Carolina Mutual Insurance Company. The company prospered and created the city’s Black middle class that resided in the Hayti District. The Mutual, as the insurance company was popularly referred to, became the economic anchor of Durham's "Black Wall Street."

A devout Christian, Austin was guided from an early age by his father William Louis Austin, a farmer, barber and gifted violinist. The proud father refused to let his children work for white people, vowing he’d rather let them starve.

Austin’s advocacy journalism went far beyond the newsroom in his fight for equality, and was a harbinger of the Civil Rights movement, decades before the era began.

In 1933, the 35-year-old Austin accompanied Thomas Raymond Hocutt, a graduate of the North Carolina College for Negroes (now NC Central University), along with two Black attorneys; Conrad Pearson and Cecil McCoy, to the registrar’s office at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Hocutt applied for admission to the all-white UNC’s pharmacy program and was denied admission by UNC dean of admissions and registrar Thomas J. Wilson, Jr., solely because of his race.

Pearson and McCoy filed a lawsuit in North Carolina’s state superior court, Hocutt v. Wilson. It was the first legal action to desegregate public higher education in the south, North Carolina Central University historian Jerry Gershenhorn, the nation’s leading Austin scholar, wrote in a 2021 edition of the North Carolina Historical Review.

“The case did not succeed in the short term,” Gershenhorn wrote in his 2018 biography, Louis Austin and The Carolina Times: A Life in The Long Black Freedom Struggle.

Still, the legal challenge launched the NAACP’s legal struggle that culminated with the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, that declared segregated public education was unconstitutional.

Austin was a close friend of Pauli Murray, the Durham-raised, Hillside High School graduate, attorney, poet, priest and groundbreaking legal theorist. In 1940, Murray, barely out of her 20s, and a friend were arrested in Petersburg, Virginia for refusing to sit in the back of a bus headed to Durham.

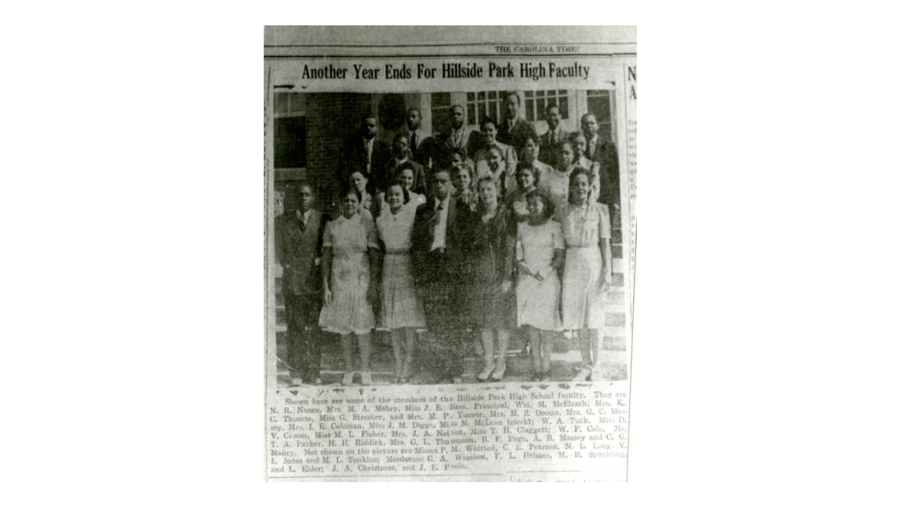

See an original clipping from the Carolina Times. Photo: Durham County Library Historical Photo Collection

When Austin heard about the arrests, he “admonished the police and praised the two women for bravely challenging Jim Crow law,” Gershenhorn wrote.

While suggesting that Murray and her friend represented a new type of Black leadership, “Austin tried to convince them to help him lead a Ghandi-like resistance movement in the city

Murray declined Austin’s offer, but the incident prompted her to enroll in law school at Howard University. Murray described Austin as “a descendant of Nat Turner and a firebrand if there ever was one,” Gershenhorn stated.

It was a heady period for the young publisher. By the 1940s, the Carolina Times had the largest circulation of any Black-owned newspaper in the state.

Austin’s Carolina Times weighed in on virtually every major American event during his lifetime.

During the turbulent 1960s, Austin chronicled the work of grassroots leaders like Howard Fuller and the legendary Ann Atwater, who both demanded suitable homes for Hayti’s low-income residents who lived in the historically Black community in the southern shadow of downtown and were ignominiously displaced by the construction of the East-West Expressway.

When Martin Luther King, Jr. was cut down by an assassin's bullet in 1968, Austin printed the fallen leader’s immortal, 1963 “I Have A Dream” speech and wrote, “The assassination of Dr. King, intended by its perpetrators to put an end to one of the greatest leaders against the practice of racial discrimination, has instead brought to their knees the consciences of every respectable and just citizen of this nation.”

Two years before he died, the activist Fuller, along with like-minded Black students at Duke University, “who wanted a curriculum that was meaningful and relevant to Black students,” started Malcolm X Liberation University (MXLU), in a warehouse in the 400 block of East Pettigrew Street, in the same block of the Carolina Times offices, Gershenhorn noted.

“Although the new university was founded on nationalist principles, which Austin, an avowed integrationist generally disparaged,” he was sympathetic to MXLU,” Gershenhorn added.

Toward the end of his life, Austin received well-deserved recognition for his work on behalf of his city and community.

One year before Austin’s death, Ben Ruffin, then a young civil rights leader and public housing activist, declared that the crusading journalist “came along 30 or 40 years before his time.”

“He is the type of Black man the young look up to and the type of man who had the courage to stick with the struggle,” Ruffin added. “He could have been a rich man and sold his soul to the white and Black establishment. Instead, he chose to stick with his people.”

Austin died of pancreatic cancer on June 12, 1971, at Lincoln Hospital.

He was inducted into the North Carolina Journalism Hall of Fame in 2008.

more stories from the African American Heritage Guide

Education in Durham From reconstruction through Jim Crow segregation to today, the history of Black Durham's educational journey is marked by triumphs over systemic racism and a commitment to excellence. Learn More