Durham's Civil Rights History

This story is a part of our African American Heritage Guide Project, a printed guide and collection of stories about Durham's Black history, culture, community and entrepreneurship created by Black writers, poets and artists. Find more stories and information about the guide.

During the 1950s and ‘60s, Durham’s spirit of defiance and resilience played a crucial role in inspiring tactical, nonviolent Civil Rights protests across the South. The city stood as the epicenter of the African American middle class in North Carolina and across the Southern region. Within its embrace was the Hayti District, a residential and social nucleus for Black life that pulsed with the heartbeat of a community. Hayti not only fostered commerce for the Black community but was the core of cultural identity and belonging. And yet, despite having this vibrant and self-sustaining social, economic, and cultural network, the tendrils of Jim Crow served as a reminder of the inferiority enforced on those who dared to dream beyond the confines of racial constraint.

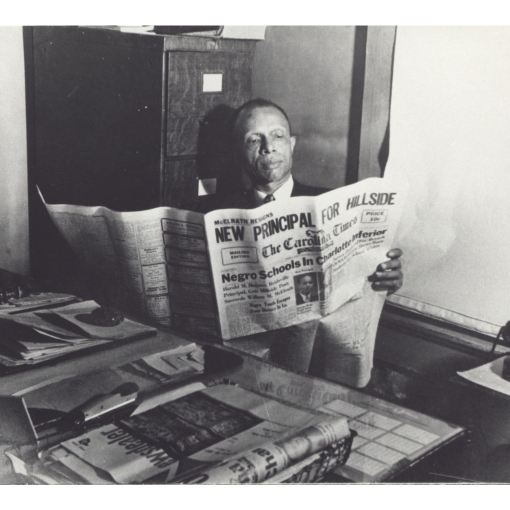

Judge Floyd McKissick took on desegregation cases and defended activists who were arrested at sit-ins. Photo: Durham County Library Historical Photo Collection

Youth-Led Activism Takes Center Stage

Resistance to Jim Crow took on various symbolic forms outside the conventional civil rights movement. Opening in 1926, The Carolina Theatre invited Black people to perform and attend shows and events, though all aspects of their experience were segregated by race. In 1944, the men's basketball team from North Carolina College for Negroes (now North Carolina Central University) engaged in a groundbreaking game against the Duke School of Medicine, marking the South's first racially integrated college-level basketball match. But by the end of the 1950s, civil rights activists grew impatient with the slow pace of desegregation. Youth, in particular, were frustrated with white resistance and Black adult leadership, urging organizations to adopt a more active and militant strategy. One of these activists was Rev. Douglas Moore of the Asbury Temple United Methodist Church.

On June 23, 1957, he took matters into his own hands and challenged the power structure by taking a group of young individuals from a church class to the Royal Ice Cream Parlor. Known as the Royal Seven, they sat in the white section and asked for service. The owner asked them to leave, but after they refused, they were arrested for trespassing. Although this early documented sit-in never led to immediate change, it inspired a new wave of African-American students to adopt Rev. Douglas Moore's approach to protesting. On February 8, 1960, driven by the desire to desegregate their city and to demonstrate solidarity with the four Greensboro students who staged sit-ins at Woolworths, twenty students from North Carolina College organized their own at the Woolworths, S.H. Kress and Walgreens lunch counters in downtown Durham.

Virginia Williams was part of the Royal Seven. Photo: Discover Durham

Martin Luther King Jr.'s Endorsement

The most influential supporter of the Durham sit-in movement was Martin Luther King Jr., who visited Durham five times. His most recognized visit occurred on February 16, 1960, eight days after the initiation of the sit-ins at the Durham Woolworths, where he addressed a crowd of about 1,200 people at White Rock Baptist Church, urging them to stay strong and to "not fear going to jail… if the willingness to stay in jail arouse the dozing conscience of our nation."

This speech, called “A Creative Protest,” motivated activists to persevere in their pursuit of justice. Although many protests during this period were spontaneous and not part of an organized plan, some innovative tactics were employed to fight against segregation, such as the round-robin tactic used by Black theater patrons, North Carolina College students, and local Black high schoolers to desegregate The Carolina Theatre. However, the activism landscape changed in the spring of 1963 when local activists organized three days of mass protests.

Dr. King visited Durham 5 times in his support of the Durham sit-in movement. Photo: Durham County Library Historical Photo Collection

The Spring of 1963

The first demonstration was on May 18, 1963, when several hundred North Carolina College students marched downtown and entered several restaurants and stores, demanding service and refusing to leave. Police officers arrested 130 of them. Immediately afterward, hundreds of Black individuals gathered in front of Durham County Courthouse, where the jailed students were held, to express their solidarity. They faced resistance from opposing white individuals holding baseball bats, broken beer bottles and cue sticks. The police called newly-elected Mayor Grabarek to the jail where he met with the movement's spokesperson, Hugh Thompson. Hugh requested food and cigarettes for the jailed protestors. When the Mayor instructed the police chief to grant this request, the crowd dispersed.

Durham's Black community members showed strength and solidarity in their ability to organize for Civil Rights. Photo: Durham County Library Historical Photo Collection

Over the next three days, protests persisted. The jail and courthouse overflowed with protestors, shoppers avoided downtown Durham to avoid the demonstrations, and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which had set up a headquarters in Durham, North Carolina in 1962, partnered with a local chapter of the NAACP to issue a statement announcing thirty days of mass demonstrations until the city met their demands. Durham had never seen such ongoing protest activity, forcing the city to address the issue. These protests changed the course of the Durham Civil Rights Movement and led to significant reforms. Within three weeks, 90% of restaurants, lodgings, cinemas, pools and libraries in Durham opted to integrate voluntarily.

Honoring the Legacy, Continuing the Fight for Justice

While significant progress has occurred since the days of Jim Crow, the legacy of structural racism casts a long shadow, shaping the experiences and opportunities of Durham's residents along racial lines. Yet, the spirit of resistance, unity and resilience that defined the Civil Rights Movement remains alive in Durham. At the Carolina Theatre, you can visit the Confronting Change exhibit to learn more about the protestors who advocated for the desegregation of the Theatre.

The John Hope Franklin Center, named after lifelong civil rights activist Dr. John Hope Franklin and inspired by his work, is dedicated to creative sharing of ideas and methodologies. Community organizers, activists, and advocates continue to mobilize for change, drawing inspiration from activists such as Ann Atwater and Pauli Murray while confronting contemporary challenges. Organizations like Communities in Partnership, Black Workers For Justice, and local initiatives for police reform, affordable housing, and educational equity carry the legacy of those who came before, amplifying their calls for justice and equality.

Visit the Carolina Theatre to see the Confronting Change exhibit. Photo: Discover Durham

As Durham continues to evolve and address the complexities of a rapidly changing world, the legacy of its involvement in the Civil Rights Movement serves as both a guidepost and a challenge. It calls upon us to confront the uncomfortable truths of our history, to acknowledge the ongoing impact of systemic racism and to continue our efforts in the pursuit of a more just and equitable society. In remembering the legacy of past activists, we honor their commitment to freedom, equality and the unyielding belief that another world is possible.

more stories from the African American Heritage Guide

Hayti Heritage Center, Then and Now “It has been my honor to serve as guiding steward of the Hayti Heritage Center, a cultural treasure rooted in the Hayti community. The Foundation has provided quality arts programming for nearly 50 years while preserving the incredible heritage of a historic venue that dates back to 1891. The city is enriched by the Hayti Heritage Center, [one of] the last remaining original structure[s] from Durham’s iconic Black Wall Street district.” - Angela Lee, Executive & Artistic Director of Hayti Heritage Center Learn More

Louis Austin: The Spiritual Architect of Durham's Black Press The history of Black journalism is synonymous with the name Louis Austin, a community member who devoted his career to "The Truth Unbridled." Learn More

Beyond Black Wall Street: Durham’s Business Legacy Beyond Black Wall Street: A journey of resilience, creativity and innovation rooted in the history and promise of Black entrepreneurship and ownership in Durham. Learn More