Hillside High School

The proud history and storied legacy of Hillside High School.

This story is a part of our African American Heritage Guide Project, a printed guide and collection of stories about Durham's Black history, culture, community and entrepreneurship created by Black writers, poets and artists. Find more stories and information about the guide.

Before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1954 outlawed segregation in public schools; there were nearly 300 all-Black high schools in North Carolina.

Today, five of those schools are still operating: James B Dudley in Greensboro, George Washington Carver in Winston-Salem, E.E. Smith in Fayetteville, and Hillside High School in Durham.

How did those five institutions manage to remain open, while hundreds more were shut down or converted into junior high or elementary schools during desegregation?

Perhaps the answer can be found with Hillside, the oldest of the high schools that today is housed in a state-of-the-art campus complex on Fayetteville Street, that was designed by acclaimed Durham architect, Phil Freelon.

Hillside, from the onset, was a pillar of Durham’s Hayti District, a historically Black community that stretches from NC 147 to Cornwallis Road.

Jean Bradley Anderson, in her exhaustively researched Durham County, noted that several years after the Civil War, the Freedman's Bureau, religious organizations and the Peabody Education Fund established a school for freedmen in [a neighborhood] that “later became known as Hayti.”

According to Hillside’s history, the school was known as the Ledger Public School, and the superintendent was James Whitted, “a highly respected man of mixed races (Black and Native American) who had managed to educate himself.”

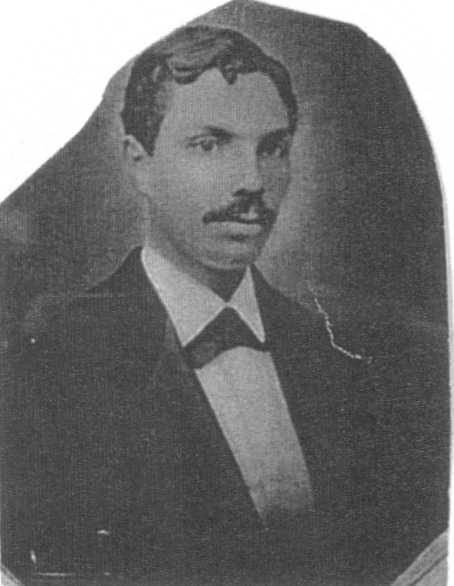

James Whitted was a revered member of the community. Photo: Durham County Library Historical Photo Collection

In 1887, the Whitted School was established as the first public school for Black students in Durham, and named in honor of its founder.

The school burned several times, in 1888, 1889, and 1896, but managed to employ a faculty of four teachers who provided instruction to 161 students who graduated from the ninth grade. By 1918, Whitted added grades ten and eleven, but burned again in 1921.

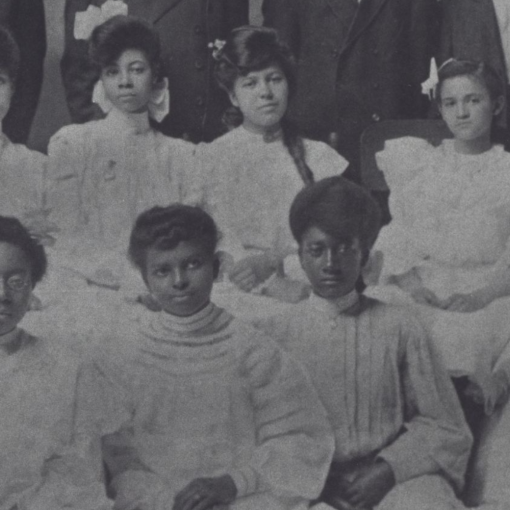

Hillside High School's roots are found in Whitted School. Photo: Durham County Library Historical Photo Collection

John Sprunt Hill, described by Patterson as a “philanthropist and ardent segregationist,” donated land for a new school at the corner of Umstead and Price streets in the Hayti District. The school was built at the cost of $125,000 and named Hillside Park High School, after its benefactor and nearby Hillside Park, according to Patterson’s work, and the school’s timeline.

By the 1930s, Hillside faced “a host of setbacks” related to its physical appearance. There were no lights in the classrooms except in the basement, “making it difficult for students to see on cloudy days. The absence of lockers left students with no choice but to carry their books and supplies the entire school day,” Patterson wrote.

In 1943, the school was officially renamed Hillside High School. The 1944 class was the first to graduate from a 12-year system. The school moved to Concord Street in 1949, and again in 1995 into the $26 million campus” on Fayetteville Road.

The legacy high school educated generations of Black students during Jim Crow, and today, while still predominantly Black, has educated a growing Hispanic population, along with a cadre of White, Native American and Indian students.

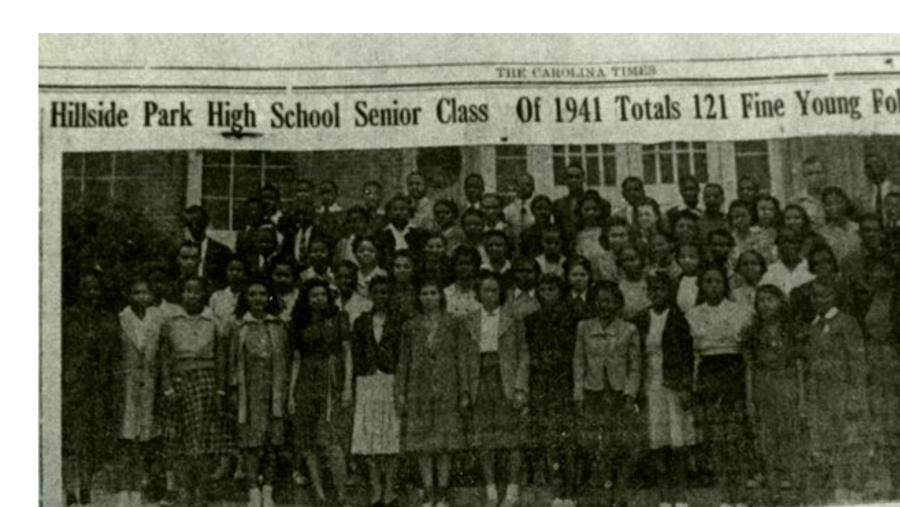

Despite multiple setbacks, the students and faculty of Hillside High School persevered. Photo: Durham County Library Historical Photo Collection

Hillside graduates have left their mark in virtually every sector of society; the arts and sciences, law and politics, civil rights and medicine, sports and fashion, finance and education.

Education scholar Gerrelyn Chunn Patterson, in her 2005 doctoral dissertation at UNC-Chapel Hill, “Brown Can’t Close Us Down: The Invincible Pride of Hillside High School," noted that Hillside remained intact during the transformative desegregation period “as a result of its protection by the politically and economically strong Black community.”

John H. Lucas, the school’s celebrated principal during desegregation said, “There was never the thought that I was aware of…that there wouldn’t be a Hillside High School.”

“We just wanted Hillside to remain Hillside,” Hillside grad and former Durham police chief Steve Chalmers said in a 2002 interview included in Patterson’s dissertation, “and we didn’t want to give up a lot of things we enjoyed as a culture.”

“Even in 1970, after Hillside enrolled White students… [there were no] substantial changes in its traditions, structure, expectations, extracurricular activities and community connections in the school,” Patterson wrote.

Before Hillside moved to its current location on Fayetteville Street, it stood at the center of the Hayti District in the southern shadow of downtown, a stone's throw from historically Black North Carolina Central University.

One hundred and two years after it was founded, Hillside continues as a beacon and bastion of inclusiveness, while celebrating more than a century of Black pride.

From its inception, Hillside High School has continued to graduate "fine young folks." Photo: Durham County Library Historical Photo Collection

Hillside’s commitment to diversity is evidenced by the school’s “Wall of Fame” that features the bronze-plated names of its top graduates from 1942 to 2022 — who are Black, White, Indian, Asian and African.

The Wall of Fame in early spring, shared space with posters written in Arabic and English, RAMADAN Mubaraka – Blessed Ramadan – To You and your Family!”

Hillside has a long history of civic engagement and activism.

Over the decades, the school has hosted community meetings to feed hungry school children during the Great Depression, in support of World War II, equal pay for Black teachers and visits by political candidates, including President Joe Biden.

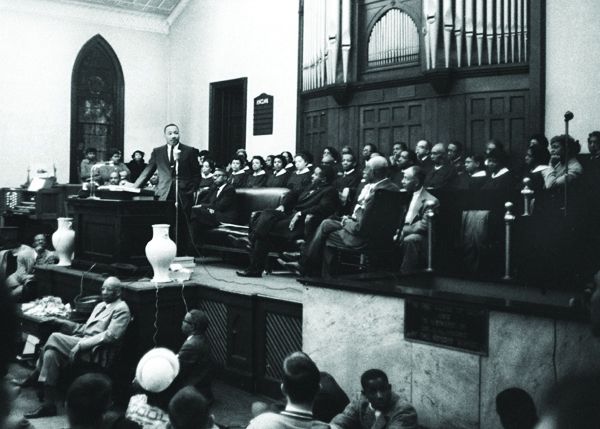

On October 7, 1956 Hillside partnered with the Durham Business and Professional Chain, a support group for Black-owned businesses to host the young Baptist minister Dr. Martin Luther King.

King’s words were prescient.

“Doors will be open to you now that were never open in the past. Be ready for opportunities,” he told the Hillside gathering.

“At its inception, Hillside was one of only two public secondary institutions for African Americans in the entire state of North Carolina,” according to the school’s Centennial Timeline.

Dr. King would visit Durham four more times after his first visit to Hillside High School. Photo: Durham County Library Historical Photo Collection

Patterson noted that Jim Crow racism, with its legal enforcement of residential segregation “prohibited African Americans from moving to neighborhoods where credit was more readily available, even if they could afford to do so.”

The end result was a model of self-sufficiency and an elegant thumb in the eye of segregation that featured a nationally recognized Black middle class and relatively affluent class powered by Black-owned institutions.

The North Carolina Mutual Life Company opened for business on August 14, 1898. The company closed its doors for good in 2022, but during its heyday, “the Mutual” was the largest Black-owned company in the world and the economic engine that propelled Durham’s "Black Wall Street."

Ingenuity and hard work led to the development of Hayti, the home of more than 400 businesses and thousands of homes that were razed by urban renewal in the 1960s and 1970s. The community reached its greatest height during World War II. Consider a now-famous description of the community’s nightlife during that period told to Anderson by Reginald Mitchner in Durham County:

“Taxi drivers made money like nobody’s business. A man driving a taxi then was averaging $150 to $200 a night, especially around payday…The place was jumping, because there were clubs and joints of all descriptions everywhere. It [almost] turned into a Vegas strip.”

Hillside has lived up to its motto; “Rebuilding and Redefining Academic Excellence!”

In 1923, after its first year of operation, it became the first Black high school in the state to receive a “Class A,” rating, according to its timeline.

During the mid-1920s, when instruction to Black students was limited to vocational skills, Hillside was led by educators like Carrie Thomas Jordan, a "Jeanes Teacher," who advocated for Black students to be taught the same subjects as White students, including spelling and geography.

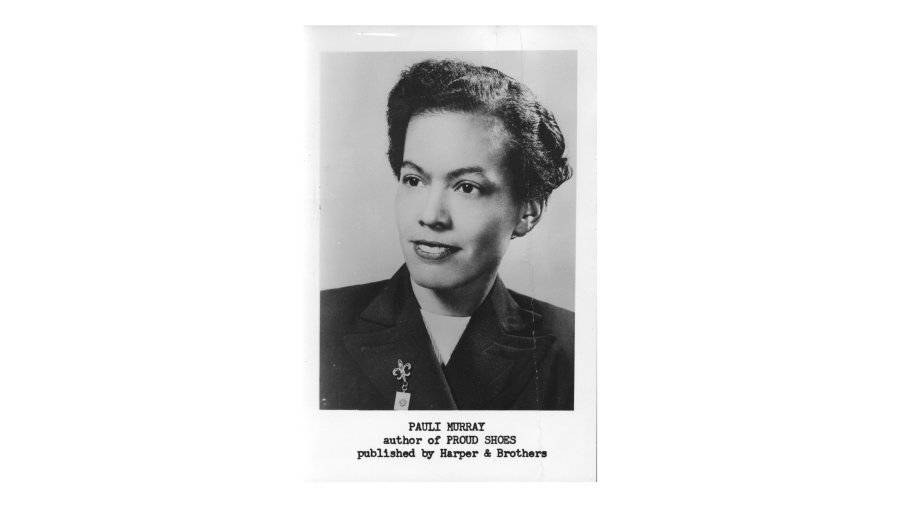

One of Hillside’s earliest students was the groundbreaking legal theorist, attorney, author, poet and Episcopalian priest Pauli Murray, who graduated in 1926 with a certificate of distinction, according to a timeline along a first-floor wall at the school.

Pauli Murray is one of the many graduates Hillside High School is proud to have educated. Photo: Durham County Library Historical Photo Collection

“Out of the 40 students in Murray’s graduating class, 17 went on to college,” the timeline adds.

In her dissertation, Patterson found that Hillside never wavered in its mission to educate Black students and “consistently reinforce the message that they were to uplift the race.”

“While the school did not receive the same funding and resources as neighboring White schools, Hillside students and staff persistently fought through such discrimination in order not only to survive, but prosper,” according to the school’s timeline.

Hillside alumni’s memories about the school are positive, and filled with pride. They describe in today’s parlance, a “safe space,” for Black people.

Hillside alumni point with pride to a school their grandparents, parents, aunts and uncles attended; and teachers “who were concerned with our full existence…My dad went there, my cousins went there, my aunt went there, practically everyone I knew went there. It was such a family tradition,” one graduate told Patterson.

“If you grew up in Hayti where I did, you were supposed to be somebody special,” another graduate told Patterson. “Hillside at that time had a reputation of being probably the best high school in North Carolina, certainly the best Black school.”

Among the school’s most-loved officials was Prof. Frank Howard Alston, who graduated from Hillside in 1937 and returned to serve as an assistant principal for 33 years.

By the time Alston retired in 1979, Alson had guided generations of Hillside students who had taken to calling him “Prop” Alston because he had been there for so long.

“Prop Alston wasn’t a big man, but he carried a big stick,” explained Elaine O’Neal, a 1980 Hillside grad who went on to become a pioneering judge and the first Black woman elected mayor of Durham.

“Mr. [John] Lucas [the principal], had a soft touch, but Prop Alston would come at you,” O’Neal added. “He’d call you into the office and tell you, ‘I know your parents. I know your brothers and sisters. I know you. I know you.”

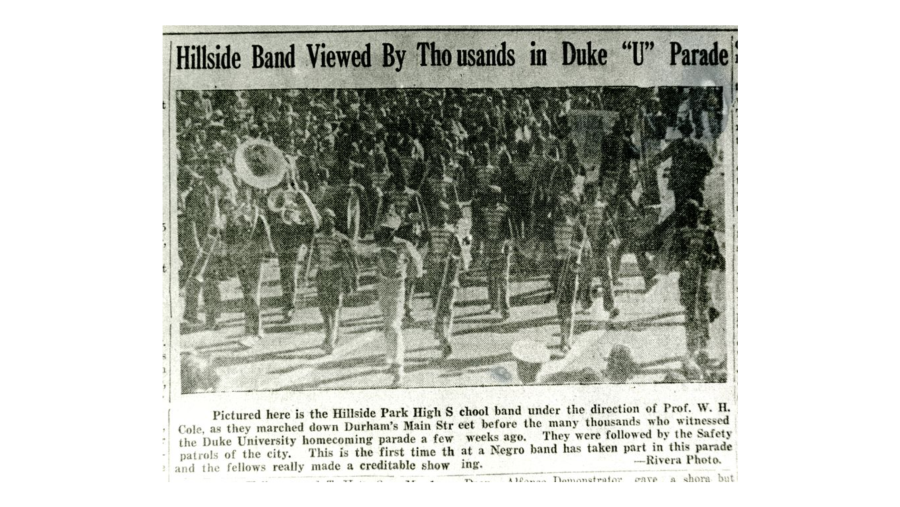

Hillside’s history features an array of award-winning extracurricular activities, including its marching band.

Hillside High School's marching band has a legendary history. Photo: Durham County Library Historical Photo Collection

“It wasn’t just the marching band, there was the symphonic band and the concert band,” said O’Neal, who played the oboe and was co-captain of the flag girls with the marching band.

O’Neal knew as an eighth-grader that she wanted to attend Hillside, so she moved in with an aunt who lived on the same street as the school.

“Gosh, it was everything,” she said about her time at the school, while adding an element often mentioned among Hillside grads: family.

Two of O’Neal’s siblings attended Hillside. So did her mother. She’s still close with the flag team members. Their children attended Hillside and were marching band members too.

“It took four buses to move us around, we were 180-strong,” O’Neal said. “We had flags, rifles, clarinets, every instrument. And if you didn’t have an instrument, [the band director] would find you an instrument to play. We only had [the director and assistant director], so the parents volunteered. That kept us safe and out of trouble. Looking back now, it was almost magical. I’m glad my son got to experience that closeness.”

Ditto for an award-winning theater arts program that achieved unprecedented heights with the guidance of retired director and educator, Wendell Tabb, whose former students include student Academy Award winner, film director Kevin Wilson Jr.; television actresses, April Parker Jones, and Lauren E. Banks; and Santron Freeman, a dancer who has worked with Beyoncé, Alicia Keys, and Mariah Carey.

“So often, Black and brown children are minimalized,” Hillside principal William Logan said in 2022 when Tabb retired. “So often, Black and brown children are sidelined. Wendell Tabb recognized what God has placed in them.”

Russel Blunt led track teams that won 10 consecutive state outdoor championships, seven indoor championships and stood undefeated in dual meets for 13 years. The Russell E. Blunt Invitational was named in his honor.

The storied 1943 state championship football team was undefeated, untied and unscored on.

The "Pony Express" basketball team of 1964-1966 bested a Laurinburg Institute team that featured future NBA Hall of Famer Charlie Scott and New York playground legend Earl “Goat” Manigualt.

The Pony Express featured its own “Goat,” John Bullock, a near-mythic player who walked off the court following a masterful athletic performance during the 1966 state championship game, and stepped into basketball lore, never to be heard from again.

From marching band to the basketball team, Hillside High School has continued to offer students top-notch extracurriculars. Photo: Keenan Hairston

The quicksilver, superbly conditioned, “Pony Express,” averaged 100 point a game in 1965, and still hold multiple team scoring records in the North Carolina High School Athletic Association record book: most 100-point games in a season with 14; highest point total in a game, a startling 147 in 1966.

The Pony Express ballboy, John Lucas, learned from the team and became a high school all-American at Hillside in basketball and tennis. Lucas later starred in both sports at the University of Maryland before a long playing and coaching career in the NBA.

In his 2009 book, 32 Minutes Of Greatness, former Pony Express player Donald McLaurin III, paints a vivid picture of playing with “a once in a lifetime dream team.”

McLaurin, with the spirit of a griot, tells the story of being a Black athlete in America during Jim Crow, and living “face-to-face with [the] indignities forced upon Black people.”

Unheralded beyond the Black sports world, the Pony Express helped usher in a new era when predominantly White colleges in the South began recruiting Black hoop stars.

“Those were some of the best years of my life, and it set the stage for everything that happened after that,” O’Neal said. “They embraced you. They trained you. Then they sent you out to do what you were supposed to do in the world.”

That unity of purpose is still evident at Hillside and binds the community together.

Then the retired judge added, “We still get together. We’re having a cookout next month.”

more stories from the African American Heritage Guide

City of Champions: A History of Black Achievement in Sports Discover the athletic legacy of Durham through the city's Black athletes, coaches, programs and establishments. Learn More

North Carolina Central University: No Ordinary, Common Barnyard Fowl “That audacious belief of our people – that in most ordinary men and women there reside the most extraordinary possibilities, and that, if we keep the doors of opportunity open to them, they will amaze us with their achievements.” Dr. James E. Shepard Learn More

Education in Durham From reconstruction through Jim Crow segregation to today, the history of Black Durham's educational journey is marked by triumphs over systemic racism and a commitment to excellence. Learn More